[ad_1]

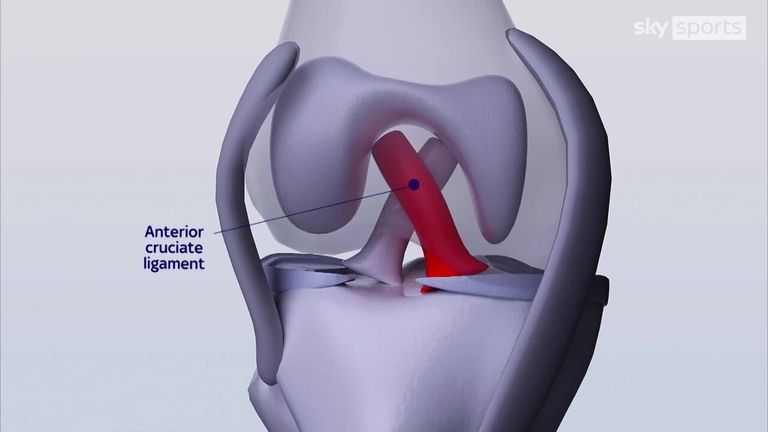

It has been the hottest topic in the women’s game – but not for welcome reasons. Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries are wreaking havoc within the sport, depriving top competitions, leagues and tournaments of some of the world’s best players.

The list of sufferers is long and the issue is far more complex than even medical experts and specialists in the field profess to understand.

Female footballers are living in fear, with the problem being anecdotally described as an ‘epidemic’.

The numbers are especially exposing. Football injuries are responsible for nearly half of all ACL reconstructions performed in the UK. They have the highest recovery burden, and account for nearly one-third of all playing time lost due to injury. The psychological load is heavy too.

In just over 12 months the Women’s Super League lost – and thankfully regained – Arsenal trio Leah Williamson, Beth Mead and Viv Miedema, while Chelsea striker Sam Kerr had her season cruelly ended in early January. Another high-profile sufferer whose absence will be keenly felt.

Then just over a month after Kerr’s injury, Chelsea lost striker Mia Fishel to another ACL injury after she only recently made a comeback from the same injury sustained in June 2022.

Consultant orthopaedic surgeon Nev Davies paints a bleak picture of a worrying trend among young people in the UK, where a 29-fold increase from two decades ago shows females to be four-to-six times more at risk.

“We are so behind the rest of the world when it comes to injury prevention… it’s embarrassing,” he says.

While female athletes across the board are more susceptible, a spate in football specific injuries has gathered concerning momentum. Data suggests over 195 elite players have been added to the casualty list in the last 18 months.

To illustrate, between 25 and 30 players – enough for an entire squad – missed the Women’s World Cup last summer because of ACL tears.

Thankfully, there is finally an acceptance that urgent action must be taken.

In December, European football’s governing body UEFA announced the introduction of an expert panel on women’s health to seek a deeper understanding of ACL injuries and their frequency among female players. About time.

“For 20 years we have known there is an increased ACL injury rate in women and girls,” Dr Kate Jackson, a renowned sports and exercise medicine specialist explained when quizzed about the clear imbalance. “There is a nuanced gender issue that needs exploring. We don’t yet fully understand it.”

So, what is causing such disproportionate rates? Why does it matter? And what steps does the sport need to take to address the disparity?

Is football failing women?

The number of female athletes who had their World Cup dreams dashed by ACL ruptures last year was exposing. The list reads like a who’s who of elite international talent.

Domestically, as far as WSL clubs were concerned, Arsenal were hardest hit. Jonas Eidevall’s side had a total of four players sidelined by ACL tears last season.

Football-focused studies, of which there are few, suggest women are six times more likely to suffer ACL injuries compared to men and 25 per cent less likely to make a full return. At present, 13 WSL players are going through recovery, including Arsenal’s Williamson, Man United defender Gabby George and Leicester winger Hannah Cain.

Associate professor of medicine at the University of British Columbia, Jackie Whittaker, has been involved in the research process and believes organisations like FIFA or global players union FIFPRO need to fund a study such as the one NBA and General Electric (who sell ultrasound machines) commissioned back in 2015, to investigate the commonality of tendon injuries in basketball.

The inquiry was designed to help inform and prevent further injury outbreaks.

“Sometimes you can get private industry saying, ‘we feel this is really important’. I think girls speaking out might increase the likelihood of that happening [in football],” Whittaker said.

FIFPRO has recently reported that increased workload, travel and insufficient rest have all contributed to higher injury rates more broadly. Makes sense, but acknowledgment and admission can only be considered phase one.

ACLs in particular continue to perplex experts – and so solving the problem remains a moving target. Physiological, biomechanical and environmental factors are all at play and range from body types, to how an athlete runs and jumps, to what quality of surface they play on – and far beyond.

Until recently, attempting to explain the impact of those factors and how they correlate has been scattergun, but perceptions are slowly changing. Stakeholders are finally taking a stand and campaigning for an in-depth look at one of modern football’s greatest failings.

Cause and effect – from far and wide

Research looking at the impact of gender bias on injury has highlighted societal attitudes to female sports participation may be affecting injury risk. Dr Jackson says “attitudes to girls being physically active, accessibility and opportunity” are all consistent themes.

Another factor is muscle strength imbalances which are more noticeable in females. This may be why structured injury prevention warm-ups that include strength and balance are so effective at reducing the risk of ACL injury in young girls. At an older age, anatomical differences in women and changing hormones during menstrual cycles have also been mooted as variable factors.

Additional theories point to women playing in boots designed for men. Female runners don’t compete in men’s trainers: why should footballers accept any different?

A recent report coordinated by the European Club Association revealed as many as 82 per cent of female players surveyed experience high levels of discomfort wearing football boots. Square pegs in round holes.

Others point towards the explosion in popularity of the women’s game and the growth in schedule as a result. Frequency of fixtures has increased several fold, and, as a result, demands and ‘load’ on athlete’s bodies is harsher; yet, female-specific sports science and access to top strength and conditioning specialists is lagging behind.

Typically, girls have not been exposed to the same elite level of training as early as boys and have not built up the same capacity or base level of strength and endurance, which increases vulnerability.

It’s an opinion shared by England and Chelsea forward Fran Kirby. “It’s important to get the basic fundamentals really young – there is a difference when it comes to how we [boys and girls] are brought up playing,” she exclusively told Sky Sports from her London home, having sat out of last summer’s World Cup after undergoing knee surgery.

“The boys are doing gym work and learning basic running mechanics at the age of six,” she continued. “When I was coaching at Reading the grassroots girls couldn’t even access a gym. The most important thing is teaching young girls the basic mechanics of being a footballer and being a sportsperson.”

‘Women are considered little men’

“There is a huge knowledge gap in the UK about the importance of injury prevention programmes… it’s embarrassing how far behind we are,” is the opinion of orthopaedic surgeon Davies, speaking about injury prevention.

His concerns are shared.

Sports medicine specialist and former Chelsea doctor Eva Carneiro is one of few females to have held a senior medical position at a Premier League club, and believes a lack of funding and knowledge is negatively impacting female athletes.

“Gender is still an issue in football. You’ve got limited funding in the women’s game and you don’t have very experienced medical teams,” she exclusively told Sky Sports. “Doctors are expensive because they are liable for every decision they make. It’s about information sharing, governance and understanding medical decisions. We’re not threats – we’re actually assets.”

On the lack of science surrounding female-specific health issues, she added: “The worse thing is – as a woman and somebody who finds the subject fascinating – 15 years ago we were trained like women are just basically small men. We ignored everything that makes a woman different.

“And yes, I think it’s to do with academia and the way we were trained and all that [needing to] shift.”

Speaking to Inside the WSL last season, female health specialist Dr Emma Ross shared similar fears: “We published a paper over a year ago which showed that, in sport and exercise science research, only six per cent of studies are done exclusively on females. There are a lot of myths out there about menstrual cycle and injury.”

Whittaker, a medical professor at UBC in Vancouver, is subsequently worried about untested speculation and emphasises the dangers of misleading messaging. She said: “I don’t want young girls to hear the message that, ‘oh, because I have my period, I’m going to tear my ACL’.

“Before we start saying the menstrual cycle or hip width is part of the risk, we need to be absolutely sure that actually is the case.”

Sadly, as the women’s game has boomed, complimentary scientific advancement and access has been forgotten. The clarion call is for “more targeted research – so a true understanding can be formed,” says Dr Jackson.

All the while, the case rate continues to soar.

‘The agent of change’

Dr Kat Okholm Kryger, a sports rehabilitation researcher at St Mary’s University, is one of few medical practitioners to take an active interest. She has published a series of papers highlighting the lack of progress in developing technology specifically for elite female footballers.

“Generally, across all research in football and sports medicine, the male has been the norm,” she told Sky News.

Dr Kryger is indeed an advocate for change. She believes safety and performance of players has been compromised for too long, because footwear and kit are still largely designed for a male physique.

Speaking exclusively to Sky Sports about ACL injuries, Dr Kryger explains the research she has undertaken does not necessarily reveal “an increase in incident rates (number of injuries per exposure hours)”, but rather exposes what she describes as “club clusters”, which are “difficult to explain”.

Her findings read: “A trend, which is not shown by the large data sets, is club clusters of ACL injuries, i.e. suddenly two to four ACL injuries within a season in a single club. This trend has been difficult to study and explain, but it is seen regularly in both the men’s and women’s game.”

Arsenal were one of the unlucky few last season.

It continues: “The number of ACL injuries seen per 1000 match playing hours ranges from 0.6 to 2.2.”

The science points to many ACL injury risk factors for women, which Dr Kryger categorises into ‘nature’ and ‘nurture’. “There are at least 30 reasons that have been discussed in literature,” she points out.

Discussed, but not addressed.

She references “body shape, hip width and the menstrual cycle” are all commonly suggested as contributing factors, but as yet, there exists “no good evidence” of the role they play, despite all being used as arbitrary excuses for why “women aren’t designed to play football.”

Nurture, in Dr Kryger’s explanation, relates to environmental factors including “less access to top quality pitches, ill-fitting boots, less access/use of gyms to aid injury prevention and less engagement with injury prevention training.”

She believes all aspects “could and should be changed”. Now it’s up to the footballing powers to listen and act.

The technology causing a positive stir

IDA: The boot revolution

Consider one issue from the realm of Dr Kryger’s ‘nurture’ argument: football boots. Footwear has, up until very recently, always been modelled on a white male.

Dr Kryger has undertaken a project to highlight the fundamental differences between a female and a male foot by using 3D scanning to map size, shape, and variations in heel and arch depth.

And she has allies. Sky Sports spoke exclusively to Laura Youngson, co-founder of IDA, a company who specialise in “high performance, comfortable footwear for female athletes.”

Youngson explained how “staggering” she found it that “women at the very top of the game” are still competing in footwear designed for the opposite sex.

She expanded: “It’s simple, we need to create footwear with female biomechanics at the heart. Take running as a sport, in terms of a case study, women’s specific running shoes have been available for years.

“Our ethos is this: functionally, can we improve performance by providing a product that is tailored? But also, emotionally, do girls feel like they exist if they walk into a shop but only have a choice of male shoes?”

Youngson emphasised the work Dr Kryger has done as central to her company’s philosophy, and the science behind providing “greater choice and access to the best equipment”.

She added: “Our focus has been on the fact women tend to have narrower heels and a wider toe area. A lot of female players suffer from sore little toes from pushing feet into boots that aren’t suited to their shape.

“Data needs to be a baseline. Dr Kryger’s research is part of why I set up the company. Women are in pain and not saying anything because they’re happy getting a free pair of boots [from commercial sponsors], but that isn’t aiding bodies or performance.

“If you take the ACL, we know surfaces and boots, and we believe there are adjustments that can be made to reduce the risk factor. Structural changes are as simple as having boots tailored to different surfaces.”

The encouraging news is quantifiable progress is also being made in the tech sector, although access to such innovation is not necessarily commonplace in the women’s game.

“We automate the process of capturing sports on video,” Patrik Olsson, CEO of video recording and analysis tool Spiideo tells Sky Sports. “We capture the game or training from multiple angles in very high resolution.”

This data pool, severely lacking in the women’s game, could be richly enhanced if commissioned adequately – it’s got the power to be a game-changer.

Spiideo is used to monitor and tag distance, speed, frequency of impact, and all the different types of transition that may precede an injury incident. “It’s the accumulation of all these things that will lead to the prevention of future injuries,” Olsson believes.

He continues: “Fundamentally, we keep track of players, and the ball, and the movements around the pitch. It’s basically digitising the game.

“There will be lots more insights coming automatically from the data – this player is getting tired, maybe we should make a substitution, or the intensity of the game is changing, which calls for something different.

“In future we will be able to see up close what is happening from a player’s point of view when an injury occurs.”

What about duty of care?

Individual clubs in the UK and US are taking matters into their own hands but uptake has been slow. Chelsea and Washington Spirit in the NWSL have both begun tracing data around players’ menstrual cycles.

Dawn Scott, director of performance, medical and innovation at Washington Spirit, says the purpose is to mitigate symptoms and help individuals train more efficiently.

Chelsea, however, are specifically targeting a reduction in soft tissue injuries, using a bespoke app to track player cycles. Speaking to chelseafc.com, manager Emma Hayes explained: “The starting point is that we are women and we go through something very different to men on a monthly basis.

“We have to have a better understanding of that because our education failed us at school: we didn’t get taught about our reproductive systems. It comes from a place of wanting to know more about ourselves and understanding how we can improve our performance.”

Sky Sports also approached a variety of physios currently working within WSL clubs, and they came to a similar conclusion: “medical provision is improving but not at a fast enough rate.”

They jointly agreed there are so many “intrinsic and extrinsic” factors affecting the ability of an ACL to perform its duty, that attempting to form rationale around one cause, or even one individual, would be impossible.

When asked if they would welcome more tailored research to guide their decision-making – helping both injury prevention and injury recovery methods – the overwhelming answer was “yes”.

Conclusion and next steps

Players have spoken. Medical experts are clear. Coaches and managers agree. Football is depriving its female players of fair and proper treatment. The institution and infrastructure, which was built to support men throughout time, is ultimately failing the women’s game – something the accelerated growth of women’s football does not legislate for.

There is, however, light at the end of the tunnel. The industry is having to sit up and listen and recommendations for change are finally trickling into the mainstream.

Chair of a new independent women’s domestic football review, Karen Carney, has published a series of improvement proposals at the behest of the UK government.

Among the key reforms in the review, published a week before the start of the Women’s World Cup, was the introduction of ‘minimum standards’ across all areas of the game. “Do I want players going on the NHS (to get treatment for injuries)? No,” Carney explained.

After speaking with players past and present, teammates and opposition, Carney also revealed many felt like “second class citizens”. They described systemic treatment as an “afterthought”.

The report calls for a new unit, funded by the FA, to research issues affecting female footballers, such as the prevalence of ACL injuries – something that has never existed in the UK before.

Former Chelsea doctor Carneiro believes it can be an “exciting time” for the women’s game, but only “if the medical profession supports players correctly, for the the first time in history.”

Indeed, what began as a bleak recital of historical failings may well blossom into green shoots of advancement.

The pathway isn’t necessarily clear – but at least, now, it exists.

For more Future of Women’s Football stories, visit Sky Sports.com and the Sky Sports app

[ad_2]